Imogen Quinn was taking notes in her virtual Origins of Modern Medicine class one day in the fall when her professor, Dr. Gordon McOuat, director of the History of Science and Technology program (HOST), mentioned a 19th century doctor. The physician, Dr. William Beaumont, conducted some astonishing experiments on the digestive system of a living patient.

“It was a point mentioned very briefly in one of Dr. McOuat’s lectures,” Quinn says. “In my mind I went—‘Wait. What?’”

So when it came time to decide on her final assignment—a choice between a standard essay or bringing to life a character or event from history in a creative way—Quinn focused on Dr. Beaumont and his patient, a voyageur named Alexis St. Martin. The man had a musket wound which Dr. Beaumont, more or less, patched up.

“There was a hole left under his left lung. It gave Dr. Beaumont a window into the gastric system. He started to put food tied to a string into the hole and pulling it out an hour later to examine how much it had been digested. It’s kind of nasty.”

Nasty for sure, but also intriguing.

“It definitely made me research a lot. I read books and articles. I found Beaumont’s book he published in 1832. That was amazing.”

Imogen Quinn

Quinn used quotes from the correspondence between the two men along with creating fictionalized letters she imagined Alexis would have written to his mother:

“How much does a man owe to another man who has saved his life? Does he owe him the remainder of his own?”

“I learned a lot about the evolution of ethics in medicine,” Quinn explains. “We wouldn’t do what Dr. Beaumont did now.”

“They are all just marvellous,” McOuat says of the assignments. “The students took them up with gusto!”

Other students created diaries, journals, a diorama, even an essay with illustrations— think graphic novel but shorter. That one was by Yuna Im. The topic was childbirth and midwifery in the early part of the 19th century.

“Childbirth became more medicalized and male physicians took over,” Im explains. “They excluded the midwives. There was a lot of misogyny. It was a change that lasted for more than a century.”

Illustration by Yuna Im

McOuat notes that, not surprisingly given the pandemic, the bubonic plague was a popular topic this year. Abby Hanson chose it as her subject and created a website for her assignment. A visit provides a timeline, causes, symptoms and treatment of the plague along with some interesting approaches to protection:

“Because physicians were expected to come in closer contact to the infected, a special garment was created to protect the physician from the disease. This costume is now one of the most recognized remnants of the outbreak … The coat is made from leather and waxed from top to bottom. The “beak” of the mask is filled with various herbs and flowers meant to purify the infected air before the physician breathed it in.”

Hanson says taking Origins of Modern Medicine this year, in these times, was ideal.

“Studying during the Covid-19 pandemic gave us a real connection to the history—to things like the plague or the cholera outbreaks in London during the 19th century.”

Faris Kapra

To smallpox, as well. That was the topic Faris Kapra chose. He created a diary of a fictitious physician working on the smallpox vaccination program in India in the 1960s and ’70s. Along with reading reports and articles about the program, Kapra started with an invaluable source of first-hand information.

“I found out that my grandfather was involved in the smallpox eradication program in Jammu and Kashmir. I interviewed him. I realized there were a lot of parallels between the struggles people are facing now with the pandemic and those that were faced during this effort to eradicate smallpox.”

Now in its third year, Origins of Modern Medicine acts as a gateway course for the Certificate in Medical Humanities launched by King’s and Dalhousie in 2020. Origins and the other courses leading to the certificate help students “think critically about medicine’s past and future roles in human life, about changing definitions of health and illness, and about the interactions that affect the patient experience.”

Im is just one course away from earning the certificate.

“It may give me an advantage when I apply to medical school,” she says. “But I really wanted to balance the science courses with the humanities. I am trying to expand my perspective. Taking these courses really helps me think more about how people engage with the medical system, how it affects them.”

Kapra is also on the certificate track. He believes Origins and the other courses to come will give him new ways to think about medicine.

He says, “The systems that are in place in medicine and the ways of thinking that we take for granted haven’t always been that way. They have been evolving in a way we can learn from. I wonder what future generations will think about this insane time in 2020?”

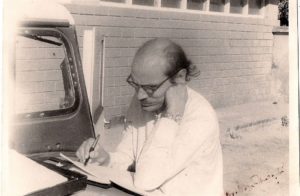

Dr. Habibullah Kanth analyzing regional data against the hood of a Jeep in a rural area of Jammu, India, July of 1976.

Dr. Habibullah Kanth

“As the state program officer responsible for the smallpox eradication program in Jammu and Kashmir, my grandfather had quite a few duties,” Faris says.

In Dr. Kanth’s words, “I had stayed at Dak Bungalow, Jammu for the night and was to tour Jammu province. The driver had parked the vehicle in the compound and had gone to have breakfast when l took advantage of the opportunities and went through statistics to make a summary. Time was at a premium and this precious commodity could not be frittered away. The basic workers did the vaccinations and collected case data, inspectors supervised, surveillance officers monitored it and CMO’s (chief medical officers of each region) transmitted their data to me. This information was compiled and analyzed by me at the state level. I also went to every region to impart orientation and training courses to all categories of workers, ranging from deputy directors to basic health workers. This wasn’t all. Much more related work was done which was quite important.”

This story was originally published in the Winter 2021 issue of Tidings.