Following a screening of the Nova Scotia-based documentary directed by Elliot Page, activists Louise Delisle and Vanessa Hartley spoke to the impact of environmental racism in their community.

Students, faculty and community members gathered in the KTS Lecture Hall on October 16 to attend the screening and discussion of There’s Something in the Water with environmental activists from Shelburne, N.S., Louise Delisle and Vanessa Hartley, who were both featured in the documentary.

The screening, put together by FYP Faculty Fellow Dr. Kathryn Lawson for the course Environmentalism: Origins, Ideals and Critique, attracted an eager and curious audience.

The documentary, directed by Elliot Page and Ian Daniel, focuses on environmental racism in rural Nova Scotia and critiques industry practices and the inaction of provincial politicians and leaders. The film brings attention to the marginalized communities affected by contaminated sites and the social justice groups and grassroots activism efforts raising awareness about this ongoing issue.

As the film begins, Page’s voice narrates scenes of children swimming and playing at the beach, families picnicking and people walking along shorelines. He introduces Nova Scotia as “Canada’s Ocean Playground,” highlighting the province’s connection to nature and water.

The serenity evaporates as the film cuts to images of boiling, bubbling and contaminated water, over which Page narrates issues of environmental harm and colonialism in the province’s history.

The film examines issues in three communities: Shelburne, A’Se’k (Boat Harbour) and Stewiacke. At each location, Page connects with local activists who are leading fights against environmental racism.

Delisle, co-chair of the Centre for Environmental Justice (CEJ) and founder of the South End Environmental Injustice Society (SEED), was the film’s first interviewee.

Delisle, co-chair of the Centre for Environmental Justice (CEJ) and founder of the South End Environmental Injustice Society (SEED), was the film’s first interviewee.

“You shouldn’t have to fight for clean water,” she says to Page in the film, as she explains the high rates of lung cancer and multiple myeloma in her community while pointing out multiple family homes inhabited by those who have been affected by similar health issues.

She shares that despite community outcry, the municipality did nothing to address concerns about air and water quality.

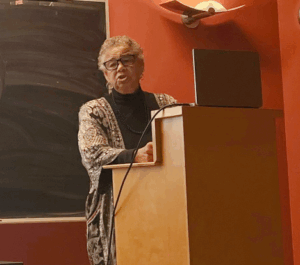

After the screening, Delisle spoke to the audience in the KTS Lecture Hall about her experience growing up beside the landfill that was forcibly placed near her community in 1942. The municipality dumped and burned all garbage from the town into the landfill, infusing the water with waste and emitting what Delisle described as “a strong smell of chemicals, burning meat, old clothes, smoke and smouldering in a cauldron of death.”

This cycle continued for decades, Delisle said, until a community member put together a petition to stop the burning in the 1990s. It wasn’t until December 2016, however, that the dump permanently closed, after SEED members made a presentation to council.

“Our natural environment, our home, around our homes and our community became very toxic…. The reason why they would neglect us all, I think, is because they didn’t have to breathe the air that we were breathing,” Delisle said, addressing the audience gathered in the lecture hall. “The leeching from that dump caused so much illness in our community that it took lives. They didn’t have to deal with that.”

Delisle’s talk was paired with a slideshow presentation, with one slide showing a family photo of eight people. She said only three of them are alive today. “Everyone else in that picture is dead from cancer.”

Silence fell across the lecture hall at Delisle’s words. “Even after the dump was closed, the systemic racism from living in the Black community in Shelburne destroyed our community.”

Delisle’s activism work inspired many people from her community to speak out about environmental racism, including Hartley, who said she would not be doing the work she does if it weren’t for Delisle.

“As I got deeper into this work, realizing how connected this was to my family was an extreme motivator,” Hartley told me after the discussion. “I have a little sister (who’s) four, and I want to ensure that when she goes into community, she doesn’t see the same thing that Louise did growing up.”

Hartley is an eighth-generation descendant of Black Loyalists who was born and raised in the African Nova Scotian community of Shelburne. She found “a deep passion for water” in 2019 after learning about environmental racism, and currently serves as the president of the CEJ, where she works alongside Delisle.

“Thank God for young people like Vanessa Hartley,” Delisle said when speaking about the new generation of activists. “She’s picking up the gauntlet and carrying on.”

In Delisle’s closing remarks, she paid tribute to “the hearts of many that have gone on,” and promised to do everything in her power to help correct the wrong done from environmental racism.

“May God bless you and enlarge your heart and open your eyes to the harm, the hurt and the hate from environmental racism, so it never happens again.”