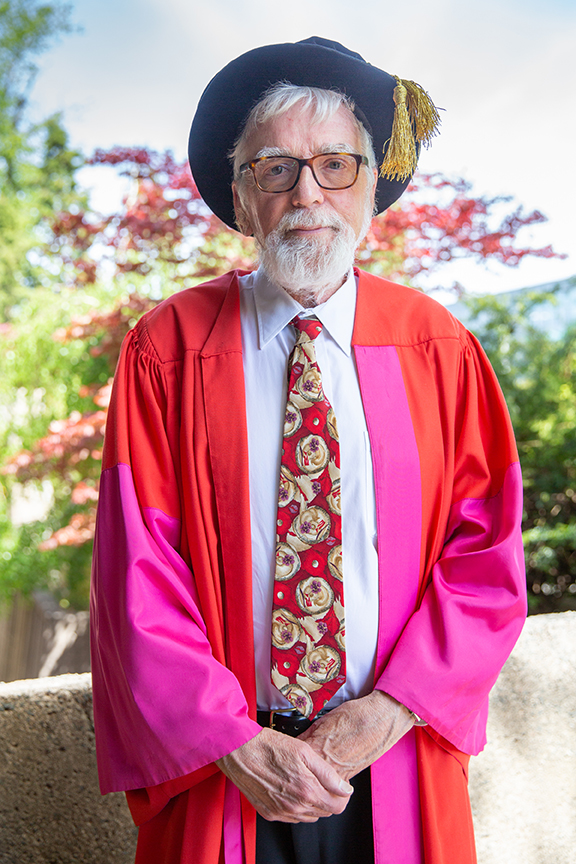

W. Ford Doolittle

Domine Vice-Cancellari; praesento vobis Guarinum Ford Doolittle ut admittatur ad gradum Doctoris in Jure Civili (honoris causa).

In an interview marking his acceptance of the 2017 Killam Prize in the Natural Sciences, CBC’s Paul Kennedy called Ford Doolittle an amphibian. The image of a glistening creature on its way from fish to fauna, taking first, flippery steps from primordial seas onto terra firma, could just possibly seem apropos to a researcher who has devoted his career to the study of genes and evolution. But what the interviewer was really trying to say is that Prof. Doolittle has learned to move between the realms of molecular biology, his home discipline, and philosophy. For Prof. Doolittle, this bridging of two solitudes has been an intellectual necessity, as well as an adventure.

In an interview marking his acceptance of the 2017 Killam Prize in the Natural Sciences, CBC’s Paul Kennedy called Ford Doolittle an amphibian. The image of a glistening creature on its way from fish to fauna, taking first, flippery steps from primordial seas onto terra firma, could just possibly seem apropos to a researcher who has devoted his career to the study of genes and evolution. But what the interviewer was really trying to say is that Prof. Doolittle has learned to move between the realms of molecular biology, his home discipline, and philosophy. For Prof. Doolittle, this bridging of two solitudes has been an intellectual necessity, as well as an adventure.

Dr. Doolittle is one of Canada’s and the world’s leading scientists. He has been a disrupter of many received opinions on the order of nature, and a revolutionary pioneer in expanding the Darwinian evolutionary model. His widely accepted theory of gene transfer at the most fundamental level of molecular life—at first harshly criticized—encourages a roots-up reimagining of evolutionary history, one that supplants the venerable ‘Tree of Life’ with a system of complex inter-organismic relationships more akin to a vast web stretched across time and space. For Prof. Doolittle, the wide-ranging implications of hypotheses such as Lateral Gene Transfer cannot be understood through a scientific lens alone, but must also be brought to the scrutiny of humanistic reflection. This conviction is what brought Dr. Doolittle, since 2007 an Emeritus Professor of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology at Dalhousie, across the campus to King’s in the first place. At King’s, the contextualization of scientific thinking within broader traditions of intellectual and spiritual history is an abiding focus of our humanities programs, and in particular our program in the History of Science and Technology. Beginning over 20 years ago, Prof. Doolittle offered something unique in the academic landscape, laying open his laboratory to our humanities students, encouraging these eager philosophical and cultural explorers to work alongside his own researchers studying “science in action”: its authorities, its practices, its aesthetics and ontologies.

Dr. Doolittle holds degrees from Harvard and Stanford Universities in Biochemical and Biological Sciences, as well as a more recent BFA in Photography from the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design. In a career that began at Dalhousie in 1971, he has published over 300 articles in the world’s leading journals. In addition to the Killam Prize, he received the $1M Hertzberg Gold Medal in 2013, Canada’s most prestigious award for science. His many other prizes and distinctions include fellowships in the Royal Society of Canada and the US National Academy of Sciences, and an honorary Doctorate from the University of Ottawa. Mr. Vice-Chancellor, in the same CBC interview already mentioned, Prof. Doolittle observed that his effort to theorize his science as broadly as possible was forcing him to “practice philosophy without a license.” Is it not fitting that we offer a scholar who has done so much to bring sciences to the humanities and humanities to the sciences an official King’s license to practice philosophy among us? For this reason, I ask you, in the name of King’s College, to bestow upon W. Ford Doolittle the degree of Doctor of Civil Law (honoris causa).

Evelyn Fox Keller

Domine Vice-Cancellari; praesento vobis Avalinam Fox Keller ut admittatur ad gradum Doctoris in Jure Civili (honoris causa).

Evelyn Fox Keller confesses that she “has something of a problem with borders,” explaining that “in [her] peculiar psychic and intellectual economy borders are meant for crossing.” In the earlier part of her career the border crossed was that between scientific disciplines. Following her Harvard PhD in physics in 1963, Prof. Fox Keller began to produce learned papers in molecular and mathematical biology, as well as in theoretical physics. Yet even as she continued her research, she began to question the intellectual frame in which the whole scientific establishment worked. At first, this was a matter of data analysis on gender imbalance amongst researchers and teachers. Argued with a characteristic clarity and rhetorical brio, articles in the early 1970s on women in science sparked widespread debate on representation and unconscious bias in the most rationalistic fields of inquiry that continues, mutatis mutandis, to this day. Yet it was the most unquantifiable aspects of gender inequality that captured Professor Fox Keller’s abiding interest, as she began to investigate the very modalities of thought, culture, and above all language, that form the interpretative nexus in which objective mathematical apparatus operate. Prof. Fox Keller’s interest in the cultural-linguistic conditions of scientific theory and practice has since extended to other areas, and in particular genetic and molecular biology, fields that interrogate our origins as a cognizant species and our coexistence in a macrocosmic continuum of life and death. In books like The Century of the Gene and 2010’s Mirage of a Space Between Nature and Nurture, her eleventh and thirteenth of a total fifteen to date, Prof. Fox Keller has put such essential questions into linguistic, philosophical, and historical context, helping her readers to question the essentializing habits of perspective that can hinder greater awareness.

Evelyn Fox Keller confesses that she “has something of a problem with borders,” explaining that “in [her] peculiar psychic and intellectual economy borders are meant for crossing.” In the earlier part of her career the border crossed was that between scientific disciplines. Following her Harvard PhD in physics in 1963, Prof. Fox Keller began to produce learned papers in molecular and mathematical biology, as well as in theoretical physics. Yet even as she continued her research, she began to question the intellectual frame in which the whole scientific establishment worked. At first, this was a matter of data analysis on gender imbalance amongst researchers and teachers. Argued with a characteristic clarity and rhetorical brio, articles in the early 1970s on women in science sparked widespread debate on representation and unconscious bias in the most rationalistic fields of inquiry that continues, mutatis mutandis, to this day. Yet it was the most unquantifiable aspects of gender inequality that captured Professor Fox Keller’s abiding interest, as she began to investigate the very modalities of thought, culture, and above all language, that form the interpretative nexus in which objective mathematical apparatus operate. Prof. Fox Keller’s interest in the cultural-linguistic conditions of scientific theory and practice has since extended to other areas, and in particular genetic and molecular biology, fields that interrogate our origins as a cognizant species and our coexistence in a macrocosmic continuum of life and death. In books like The Century of the Gene and 2010’s Mirage of a Space Between Nature and Nurture, her eleventh and thirteenth of a total fifteen to date, Prof. Fox Keller has put such essential questions into linguistic, philosophical, and historical context, helping her readers to question the essentializing habits of perspective that can hinder greater awareness.

Currently Professor Emerita of History and Philosophy of Science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Dr. Fox Keller holds more than a dozen honorary degrees and has received numerous other awards—including MacArthur and Guggenheim Fellowships, the Blaise Pascal Research Chair and the Bernal Prize for Social Studies of Science. Most recently, she was honoured with Tel Aviv University’s 2018 Dan David Prize for “innovative and interdisciplinary research that cuts across traditional boundaries and paradigms.” Prof. Fox Keller’s affinities with King’s programs is obvious, and indeed in her writings, she is a constant, virtual presence in our History of Science and Technology curriculum. In 2014, she played guest to our HOST as a Situating Science Visiting Scholar. Mr. Vice-Chancellor, for her contribution to knowledge at the intersection of science and humanities and to her work as a feminist critic of science, let us welcome Evelyn Fox Keller again, this time not as a visitor, but as a permanent resident in our house of convocation. In the name of King’s College I ask you to bestow upon Evelyn Fox Keller the degree of Doctor of Civil Law (honoris causa).

Duncan McCue

Domine Vice-Cancellari; praesento vobis Duncanum McCue ut admittatur ad gradum Doctoris in Jure Civili (honoris causa).

Much learning at King’s is centered around the hearing, shaping, and telling of stories. For our journalism students, this is an everyday reality that could pass without comment. For students in our upper-year programs, whose work is so much about the proper coordination of ideas within the ebb and flow of history, it is true in a different, if no less essential way. As a Foundation Year student in the late 1980s, Duncan McCue was acutely aware of the inherent power of narratives to shape the identity of whole cultures. An Anishinaabe of the Chippewas of Georgina Island First Nation in Ontario, he recently wrote of his FYP experience that he “wanted insight into the mind of the colonizer,” understanding that the brute force and sophisticated weaponry of settlement in the Americas was supplemented by “the deft use of laws, legislation, and literature” with “roots in Western thinking and philosophies.” As the celebrated journalist he has become, Mr. McCue continues to speak to the weight of responsibility that lies on those who construct and consume narratives, especially in their relationship to those who provide their subjects.

Much learning at King’s is centered around the hearing, shaping, and telling of stories. For our journalism students, this is an everyday reality that could pass without comment. For students in our upper-year programs, whose work is so much about the proper coordination of ideas within the ebb and flow of history, it is true in a different, if no less essential way. As a Foundation Year student in the late 1980s, Duncan McCue was acutely aware of the inherent power of narratives to shape the identity of whole cultures. An Anishinaabe of the Chippewas of Georgina Island First Nation in Ontario, he recently wrote of his FYP experience that he “wanted insight into the mind of the colonizer,” understanding that the brute force and sophisticated weaponry of settlement in the Americas was supplemented by “the deft use of laws, legislation, and literature” with “roots in Western thinking and philosophies.” As the celebrated journalist he has become, Mr. McCue continues to speak to the weight of responsibility that lies on those who construct and consume narratives, especially in their relationship to those who provide their subjects.

Best known to Canadians as an award-winning investigative journalist, author and radio host, Mr. McCue graduated from King’s with a BA in English before taking a degree in Law at UBC. His work with the CBC Aboriginal Investigation into missing and murdered Indigenous women won the Hillman Award for Investigative Journalism. An advocate for rethinking and rebuilding the relationship between Indigenous Peoples and non-Indigenous Canadians, McCue has been a leader in challenging schools of journalism—King’s included—to follow the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s calls to action by incorporating the principles of reconciliation into their curricula. An adjunct professor at the UBC School of Journalism, McCue was awarded a Knight Fellowship at Stanford University in 2011, where he created an online guide called Reporting in Indigenous Communities, built on the theme of “Helping Journalists. Decolonizing Journalism.” He was also recognized by the Canadian Ethnic Media Association for developing Indigenous issues curricula. Mr. McCue is the author of 2016’s The Shoe Boy: A Trapline Memoir, recounting a summer spent in a Cree hunting camp as a teenager.

Mr. McCue advises his journalistic peers that “telling a story is not the same as taking it.” As deeply-informed narrative wisdom, the application of this dictum extends much further than the practice of journalism in Indigenous contexts. It suggests that in our lives of study as much as in our lives as citizens, we must be careful not to control narratives to the detriment of others, at the same time that we must avoid putting such unselfconscious faith in our narratives that they begin to control us.

When Duncan McCue finished his Foundation Year, he realized that he had not closed the covers on the narrative of Western culture, but that the story would have to be told and told again, its contours altered by the cross currents of other stories whose proper force grows with their own repetition. Mr. Vice Chancellor: for his leadership in story telling, for educating Canadians, journalists and schools of journalism on the realities of Indigenous life in Canada today and for his role in promoting understanding and reconciliation, we say chi-miigwech, thank you very much. I ask you, in the name of King’ College, to bestow upon Duncan McCue the degree of Doctor of Civil Law (honoris causa).

Nicholas Hatt

Domine Vice-Cancellari, te orant obsecrantque professores doctissimi Universitatis nostrae ut Nicolaus Hatt ad munus officiaque sociorum (honoris causa) venerabilis Collegii Regalis admittatur.

Oh, you may not think I’m pretty,

But don’t judge on what you see,

I’ll eat myself if you can find

A smarter hat than me.

You can keep your bowlers black,

Your top hats sleek and tall,

For I’m the Hogwarts Sorting Hat

And I can cap them all.

There’s nothing hidden in your head

The Sorting Hat can’t see,

So try me on and I will tell you

Where you ought to be.

It is indicative of the compassionate, proactive, and occasionally tough empathy that Nick Hatt had with King’s students that his first residence position was as Don of Middle Bay. That is the residence building that features a sculpted hero Aeneas as he flees his burning city and heads into bitter exile. During Nick’s four-year tenure as a Don, and then, from 2009 to February of this year, as Dean of Students, he worked tirelessly to ensure that King’s was a place where everyone could be at home, and that no one, whether an international student travelling from afar or a city day student from just around the corner, would feel the chill of alienation. Dean Hatt’s leadership in making King’s not just a safe place to live, but also a nurturing garden for the life of the mind, was fed by the conviction that friendship lies at the heart of our academic community. This was evident in Nick’s uncanny ability, as King’s own “Sorting Hatt,” to match roommates yet unseen into partnerships that often far outlast the residence year. It was also evident in his mentorship of dons and in his wise collaboration with faculty, staff, and administration. The magic of Dean Hatt’s pastoral role at our College was his recognition that no matter our diversity of backgrounds, goals, roles, or opinions, “we are all,” to repeat his favourite saying, “in this together;” that care for one another collects us and sustains us as a collegium.

It is indicative of the compassionate, proactive, and occasionally tough empathy that Nick Hatt had with King’s students that his first residence position was as Don of Middle Bay. That is the residence building that features a sculpted hero Aeneas as he flees his burning city and heads into bitter exile. During Nick’s four-year tenure as a Don, and then, from 2009 to February of this year, as Dean of Students, he worked tirelessly to ensure that King’s was a place where everyone could be at home, and that no one, whether an international student travelling from afar or a city day student from just around the corner, would feel the chill of alienation. Dean Hatt’s leadership in making King’s not just a safe place to live, but also a nurturing garden for the life of the mind, was fed by the conviction that friendship lies at the heart of our academic community. This was evident in Nick’s uncanny ability, as King’s own “Sorting Hatt,” to match roommates yet unseen into partnerships that often far outlast the residence year. It was also evident in his mentorship of dons and in his wise collaboration with faculty, staff, and administration. The magic of Dean Hatt’s pastoral role at our College was his recognition that no matter our diversity of backgrounds, goals, roles, or opinions, “we are all,” to repeat his favourite saying, “in this together;” that care for one another collects us and sustains us as a collegium.

A native of Chester, Nova Scotia, Nicholas Hatt first came to King’s as a FYP student in 1997. He tried to leave after his first year, but found that the questions opened for him in community could be best answered only by returning to it. He has left us again to take up a new pastoral role at St. George’s Anglican Church in downtown Halifax, but his traces in the King’s symbiosis are strong, and beckon. Mr. Vice-Chancellor, for his long and caring service to King’s students and to the whole community, I ask you to join Father Nicholas Hatt in honorary Fellowship to us, ensuring that wherever he may be, he will never be an exile.