On March 30, the University of King’s College hosted a reading and panel featuring three faculty who teach in the Foundation Year Program (FYP): Dr. Roberta Barker, Dr. Laura Penny and Dr. Thomas Curran. The event was organized to celebrate the hundredth anniversary of a text frequently on FYP’s reading list: T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land, published in 1922. The event began with the reading, which included Prof. Luke Franklin, Dr. Maria Euchner and Dr. Neil Robertson in addition to the panelists.

Poetry is a medium well-suited to reading and the broad range of emotion it evokes is often best captured through engaged speakers, which King’s more than provided. Students were invited to follow along in their own books, which in true King’s fashion, almost everyone brought. Euchner, Barker, Robertson and Franklin all contributed to the reading.

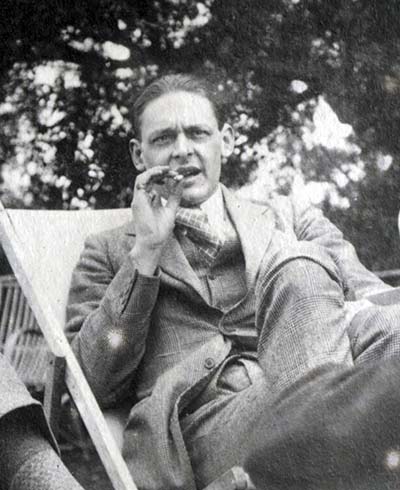

T. S. Eliot in 1923, by Lady Ottoline Morrell

Afterwards, Barker reflected on the nature of editing, bringing out a copy of The Waste Land: A Facsimile and Transcript of the Original Drafts. She spoke on drafts as the physical manifestations of relationships and the ways in which the past is never truly past. The Waste Land represents an eternal oscillation between the fear of our self’s destruction in a relationship and the absolute longing for human connection.

Curran followed, speaking of The Waste Land’s history with FYP as a text that has often occupied the reading list. He also touched on the sheer density of the poem in content, which reinforced the value of the event as another way to process the text after FYP’s schedule had moved on. Curran also spoke of the references contained within the poem, numerous as they are.

Penny was the final speaker, discussing the ways The Waste Land can be interpreted as a mirror to the world it was produced in, as well as its implicit question: how do you navigate a new world? For Eliot, it was a world post-World War I, where everything was faster and more technological. For the generation of students reading Eliot for the first time, it is a world where the pandemic remains one pressing concern among many. Our relationship to tradition changes as what constitutes ‘tradition’ does, but the questions remain much the same.

A Q&A session took place after the individual speakers. An audience member inquired about the edits made to The Waste Land by Ezra Pound, Eliot’s mentor, and the panelists discussed the alternative versions of the final text. They also spoke on Eliot’s particular brand of staging, as well as the interpretation of “The Chess Game” as a transcribed conversation between Eliot and his first wife Valerie Eliot. Other topics touched upon included the role of Grail legends in the text, how external media related to the poem then and how it does now, as well as more personal aspects of Eliot’s existence and work—including, but not limited to, the way he wore green makeup to appear sicklier. (Anyone familiar with the Broadview Edition’s photo of Eliot can attest that this effort was unnecessary.)

Eliot begins The Waste Land with the line “April is the cruellest month.” His definition of cruel is, in the context of that first passage, a world that is growing, but with difficulty. Perhaps I interpret Eliot with more optimism than intended, but poetry is a medium which invites engagement, and this is mine—seeing good things ahead after hardship. When he speaks of lilacs emerging from the frozen ground, it is an image that transcends all the years that have passed since he wrote it. As we move into the summer, students are dissipating, returning home, and considering the knowledge they’ve accumulated over the academic year. April concludes our time at King’s until September, just as it began Eliot’s text.

Franklin started the event with a quote by Ezra Pound: “Eliot’s Waste Land is, I think, the justification … of our modern experiment, since 1900.” And what a justification it is.