Many student societies are back to hosting in-person gatherings this year—often their first since 2020—and if the first meeting of the HOST Experiments Club is anything to go by, there is no shortage of interest in these events.

Late in the day on October 4, students packed into the second-floor seminar room in the New Academic Building. Within a few minutes, seats filled up and the meeting became standing-room only, as students eagerly awaited third-year biology student Ana Luiza Furtado de Medeiros’s presentation, “Pre-Colonial and Colonial Brazil: History and Food”.

Furtado is pursuing a History of Science and Technology minor and is taking Professor Mélanie Frappier’s “Hypatia’s Daughters: Women in Science”. The class includes a “bake-off” portion in which students make food using a historical recipe. Furtado decided to make a cassava cake, something she ate growing up in Brazil.

“I try to tie in my culture as much as I can with the projects I’m working on,” Furtado explains.

She wanted to provide some historical context to the cassava cake, so she began research and stumbled across a book entitled Delicias do Descobrimeto: A Gastronomia Brasileira no Século XVI (trans. Delights of Discovery: Brazilian Gastronomy in the 16th Century). She soon discovered all sorts of information she knew probably wouldn’t make it into her project, but it was too fascinating not to share.

“I emailed Mélanie and I said, ‘hey, give me a time limit, otherwise I will talk about this for hours,’” she says. Her professor supported her and suggested she present her research at a HOST Experiments Club event, so she could talk about everything she wanted to.

The HOST Experiments Club was born shortly before the pandemic, as a result of curious HOST students wanting to try out some of the scientific experiments they were reading about in class.

“It was created by students who wanted to, I kid you not, do [genetic] manipulation of bacteria,” Frappier explains. The students bought a kit and began experimenting on E.coli. Another time, they made their own microscope lenses. After that, they recreated medieval paint. It goes without saying that a presentation on the history of the cassava fits right in.

Furtado began her presentation with a brief background on Brazilian colonization. She then transitioned into several Indigenous food staples mentioned in Delicias do Descobrimento. These included the caju (cashew), goiaba (guava), camarâo (shrimp), milho (corn) and jacaré (alligator), among many others. These foods were not only significant to the many Indigenous tribes of pre-colonial Brazil, but they are still enjoyed today. For example, many people drink cashew fruit juice, she explains, adding that it has a curious quality that wrinkles your tongue like a prune.

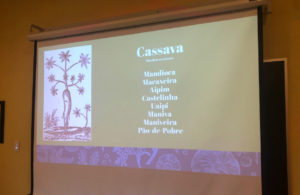

The cassava has a special place in Brazilian cuisine. It’s a thick starchy root with strikingly white flesh inside. Domesticated 4000 years ago, it’s remarkably versatile. Virtually anything done with the potato can be done with cassava. It can be ground into a gluten free flour, which can substitute wheat flour in most recipes. It can even be used to make wine. There’s only one caveat to the cassava: uncooked, this tasty little tuber is highly poisonous.

This fact was the focal point of Furtado’s presentation. Using innovative methods of drying, mashing and boiling, Indigenous women in pre-colonial Brazil devised ways to leech the high levels of hydrogen cyanide from the cassava, turning it into a long-standing staple of the local diet. Globalization saw the cassava imported to other parts of the world and now it’s also an essential food item in many parts of Africa.

This fact was the focal point of Furtado’s presentation. Using innovative methods of drying, mashing and boiling, Indigenous women in pre-colonial Brazil devised ways to leech the high levels of hydrogen cyanide from the cassava, turning it into a long-standing staple of the local diet. Globalization saw the cassava imported to other parts of the world and now it’s also an essential food item in many parts of Africa.

“In fact,” Furtado says, “The only place I could find cassava flour in Halifax was at an African grocery store.”

Furtado provided two foods she’d made: a cassava cake and fried cassava flour. The cake was lightly sweet, crumbly and soft while the fried flour was crunchy and toasty and melted on the tongue. As with anyone replicating a family recipe, Furtado insists that her mother makes these dishes better than anyone.

A Q & A session concluded the presentation, where the passionate and enthusiastic audience asked not only questions about the presentation itself, but modern-day Brazilian food.

“I’m just glad so many people showed up,” Furtado reflects. “I was expecting it to be like, my boyfriend and the two friends that said they were going to come. I’m just really glad that this many people were excited to hear me talk as much as I was excited to talk about this kind of stuff.”