From August 7–10, dozens of academics from around the world traveled to King’s campus for the Circulating Knowledge: 20 Years On conference.

During those four days, scholars attended presentations, conversed and socialized at an event that was brought together by the herculean effort of the organizing staff and faculty—in particular, Megan Krempa, BA(Hons)’22, Associate Professor of the Humanities Dr. Mélanie Frappier and Inglis Professor Dr. Gordon McOuat.

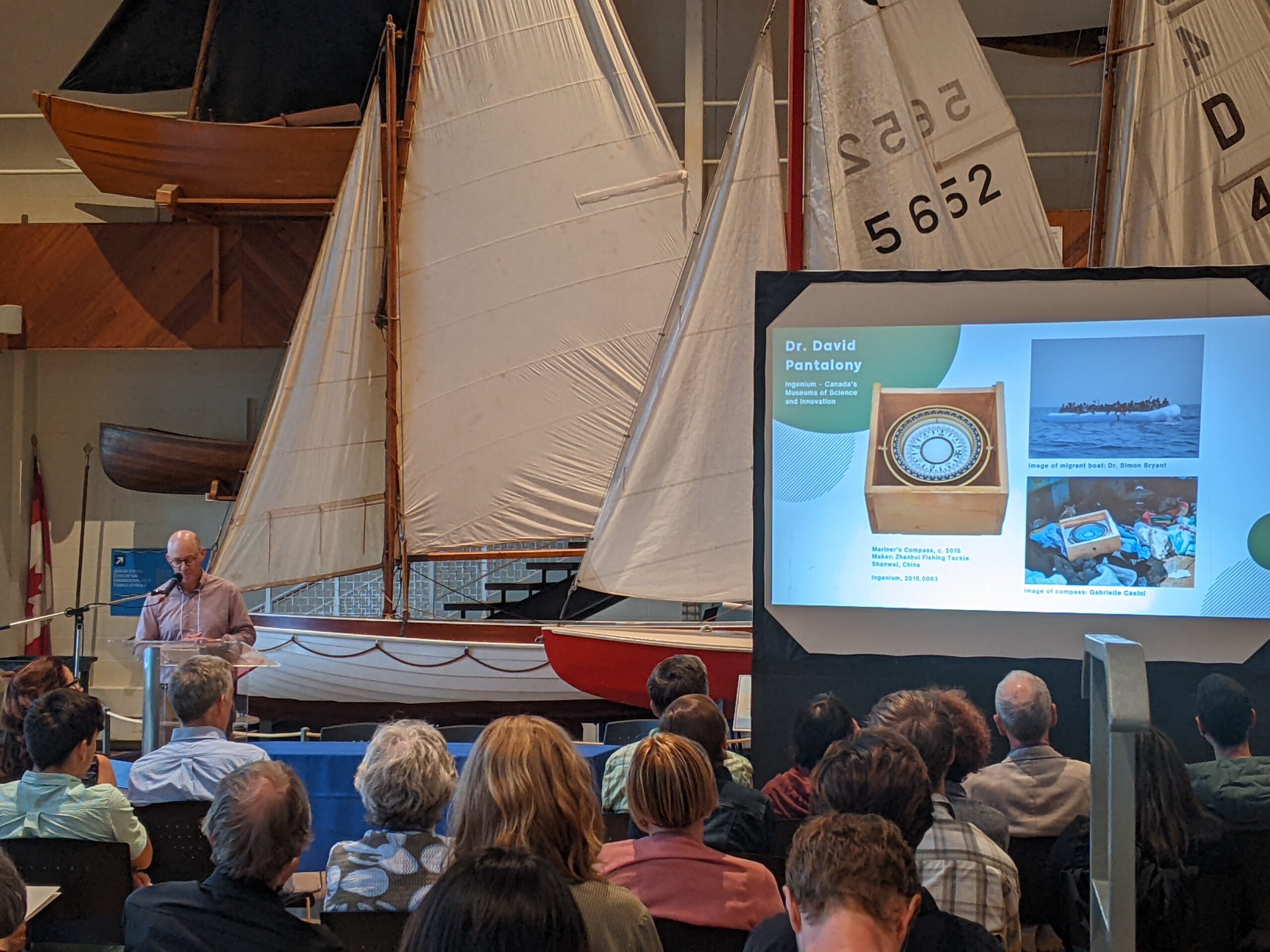

A lively reception at the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic kicked off the conference on Wednesday night. The keynote presentation focused on the newly launched “Circulating Knowledge Virtual International Exhibit,” a digital catalogue where scholars anywhere in the world can contribute to the ever-expanding field of material history and culture. The exhibit presents a bold and encouraging vision of the future of the history of science, which fully embraces the maturing digital humanities field.

Photo by Dani Inkpen

The first plenary session on the following day, “Seven Questions for the History of Science” was delivered by James Secord and acted as a bridge to the original conference in 2004. Secord’s paper, “Knowledge in Transit,” is an anchor for, and summation of, the sentiments that drove the original Circulating Knowledge project. In it, Secord suggested that a notion of “science as communication” may give some new focus to the historiography of science considering the radical transformation that the field was undergoing at the time. Twenty years later, Secord believes the questions that science historians must grapple with have largely changed.

The plenary sessions featured several impressive speakers who tackled engaging topics, such as Elise Burton’s “Rethinking Forms and Scales of Scientific Collaboration” and “Notes from Another Shore: Thinking about Global History of Science,” by the former President of the History of Science Society Fa-Ti Fan. Smaller break-out sessions made up the bulk of the conference’s time. My personal highlights include Osama Eshera’s “New Perspectives on the Medieval Arabic Tradition of Problemata Physica,” a fascinating look into how ancient Greek texts influenced and arrived to us via Islamic authors. The presentation highlighted how the careful study of these Islamic translations helps develop a more accurate understanding of the original Greek texts. On a similar note, Cosimo Calabrò’s “English Anatomical and Scientific Body through Translation” was a wonderful look into the intricacies of and disputes about the techniques used to translate scientific texts. Translating is a difficult business. As Calabrò remarked to me in a conversation afterwards, to accurately translate the meaning of a text, one must become a historian of that period.

Tuning in online, Javier Poveda-Figueroa’s “The Importance of Casa de la Cultura del Ecuador [The House of Culture of Ecuador] in Creating and Transmitting Knowledge” was a thought-provoking reflection on the role that government plays in the development and shaping of academia. And, on the topic of material history, Christopher DeCou’s “Science Revolves: Qi Yanhuai and Chinese Mechanical Celestial Globes” was a fascinating look at how technology is shared, adopted and transformed as a consequence of the exchange of knowledge through goods.

Chinese history of science was also in the spotlight during the plenary session chaired by Arun Bala. “Exploring the Relevance of Needham’s Legacy for Global Science Studies: Problems and Prospects” boasted the likes of Raymond W. K. Lau, Marta Hanson, Robin Yates, Gregory Blue and Peter Lee, Chairman of the Joseph Needham Foundation for Science and Civilization in Hong Kong. For some of us, the uninitiated, the session provided a thoughtful introduction to Joseph Needham, his relevance to the history of science in China and his own work on the topic. Famously, Needham worked on the question of why China had not become the same sort of technological wellspring as Europe, despite its earlier sophisticated societal and scientific development. Needham had served as an important bridge between the intellectual communities of Britain and China.

On the second-to-last day, Mi’kmaw Elder Dr. Albert Marshall addressed the topic of Etuaptmumk, two-eyed seeing, which stresses the importance of the dialogue between Indigenous and non-Indigenous knowledge seekers. Values in science is a flagship topic in the history and philosophy of science. And, at least for me, Elder Marshall’s talk served as a reminder of the urgency of ensuring that these values are informed by Indigenous perspectives. Increasingly, it is recognized that science, both in its development and the fruits of its employment, is a political enterprise.

At the closing plenary session, attendees were invited to reflect on the history of science as a discipline and what can be done to make the field more accessible, inclusive, international and financially sustainable—inspiring further thoughts and actionable tasks for visiting scholars returning to their respective corners of the world, equipped with a plethora of new ideas, connections and fond memories.

Dr. Marshall’s talk is temporarily available for viewing. Please enjoy.