Every year, students in the Foundation Year Program (FYP) embark on a journey that takes them through history and across cultures. This journey takes shape through reading, discussing and writing about books.

The FYP book list—and the journey it maps—evolves over time. At the end of each academic year, FYP faculty come together to re-evaluate the reading list: taking into account student feedback, some works are added to the book list while others are removed. This process keeps the syllabus relevant and increasingly diverse.

Below, three FYP faculty discuss some of the books that have been added to the 2021/22 FYP Book List.

Associate Professor Eli Diamond on Sophocles’ Ajax:

Dr. Eli Diamond

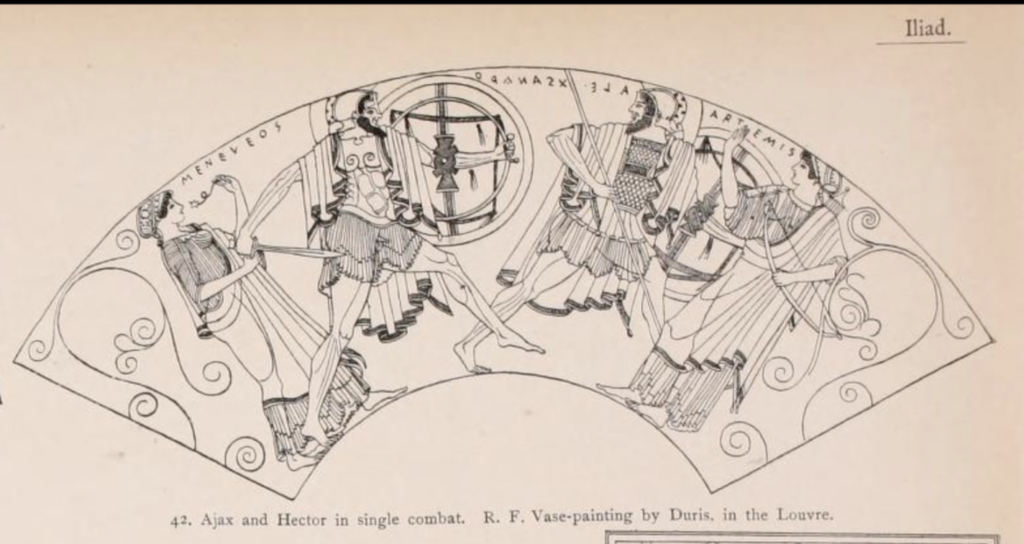

This year the Greek tragedy we will study in FYP is Ajax by Sophocles. The play is about Ajax, perhaps the pre-eminent example of the great, courageous, powerful, passionate, and fiercely independent warrior who is willing to sacrifice himself for his community so long as it recognizes his special excellence. This recognition is publicly denied Ajax before the play even starts, when the very community he has always defended decides to award the armour of Achilles after his death to the clever Odysseus over the brave Ajax. The play is about Ajax’s humiliation, but also about Odysseus, who witnesses the pain, alienation, madness, and death of Ajax, gradually coming to understand the essential role Ajax and men like him must play in a community. The play offers a wonderful way to consider the transition from archaic Greece and its semi-divine heroic kings to the democratic Athenian city of the 5th century BCE. When the virtues and characteristics required of leaders have changed so dramatically under a democratic regime, what place is left for the passion and power of great warriors like Ajax? In addressing this question, Sophocles’ play offers perhaps his most profound reflection on two themes which permeate all his works—the nature of time and the nature of friendship.

Detail from the Pictorial Atlas to Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, by R. Engelmann and W.C.F. Anderson; 1892; H. Grevel, London.

Senior Fellow in the Humanities Michelle Wilband on Shakespeare’s Troilus and Cressida:

Prof. Michelle Wilband

Shakespeare is, perhaps, the most widely familiar author on the entire FYP roster, given the privileged position of his plays in school curricula all over the world. While this familiarity might serve to facilitate our encounter with his works, it might also create predetermined expectations that distort or impede our access to them. Troilus and Cressida is in many ways the ideal play to overcome this problem. Not only is it one of Shakespeare’s most obscure plays, and so is not likely to have been assigned to students at an earlier point in their education, but the play itself takes deliberate pains to defamiliarize and estrange its content from the audience. Revisiting the most foundational and well-worn narrative in the western literary tradition—namely the Trojan War myth—Shakespeare riffs on tropes and characters that by Section 3 will also be familiar to FYP students, but will appear in this work in surprising and new ways. Neither a tragedy nor a comedy, Troilus and Cressida is most often called a “problem play,” and it delights us in a similar way to a brain teaser, by presenting us with genuinely challenging problems, and refusing to pander to our immediate expectations.

Wood engraving based on the Felton portrait of Shakespeare, believed to be from the 19th C.

Foundation Year Program Director and Assistant Professor of Humanities Daniel Brandes on Anne Carson’s Norma Jeane Baker of Troy and Aime Cesaire’s A Tempest:

Dr. Daniel Brandes

In the final section of the program, we are finally able to cast our eyes back over the course of our investigations and to trace the outline of our own conceptual horizons. A number of our contemporary works—new additions to the FYP curriculum—will explicitly take up traditional themes, figures, or characters, and measure the distance between their own epochs and our own. Just as Shakespeare revisited and re-appraised the Trojan War myth, illuminating—and being illumined by—the ancient wisdom, so the Canadian poet, Anne Carson, returns once more to this enduring resource in her creative play, Norma Jeane Baker of Troy. Juxtaposing Helen of Troy, the “face that launched a thousand ships,” with her contemporary avatar, Marilyn Monroe, Carson poses anew important questions regarding translation, historical transmission, and the meaning (and fleeting) of mortal beauty.

Aime Cesaire. Photo by Jean Baptiste Devaux, CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

And Shakespeare, endlessly sustaining, is again at issue in Aime Cesaire’s provocative, post-colonial play, A Tempest, which casts a critical eye on Prospero’s aspirations to sovereignty—over himself, his fellows, and his world—and gives pride of place to Caliban, the colonial subject, whose inherited language is at last turned against his self-styled benefactor.