FYP Letters is a series of non-curricular notes to keep us in touch over the next days and weeks. They are a combination of original writings and archival ones, including some re-printed FYP News items. — Dr. Susan Dodd, Interim FYP Director.

Foundation Year Program

Concluding lecture, 1981

Philosophy and Poetry

The presentation of a concluding lecture is a very intimidating business for the lecturer. One feels that such a lecture ought somehow to gather in and sum up everything that has gone on in the course, from the beginning to the end; and when one recalls that we have spent a year considering a vast range of the greatest literary and artistic works of western civilization, from Homer to Heidegger, any attempt to “sum up” must inevitably appear superficial and foolhardy.

Even if one considers only the final section of the course, how on earth can there be any “summing up”? What can we possibly “conclude” from what appears to be a bewildering array of diverse and conflicting positions: Einstein and Jung, Heidegger and Schweitzer and Solzhenitsyn, Bölsche and Nolde, accounts of conflict and revolution in the arts and sciences, deep divisions between scientific and humanistic perspectives, revolution in social and psychological theory, and so on? Can there be any rational conclusion from all this? Or should one sum it up as Emil Nolde does, in the final words of our Handbook:

Autumn storms came. The sea was wild. Even our Baltic Sea which is so mild at other times grew wild. We migrating birds raised our wings for the flight.

That might be a kind of poetic summing up of the chaos in which we seem to find ourselves.

No doubt you have all been considering these questions for yourselves, and perhaps you have come to some conclusions of your own. Certainly, I can’t even attempt to sum it all up in one lecture, or even in many lectures. What I want to attempt is a more modest—though still formidable—enterprise. I want to single out one dominant theme, or thread, which seems to me to run through all this recent literature, and try to see that theme in the perspective of the history which has gone before, the history from which it comes.

I think a good place to begin is with Albert Einstein’s “Autobiographical Notes”, where he tells us of his “first attempt to free [himself] from the chains of the ‘merely personal’, from an existence which is dominated by wishes, hopes and primitive feelings. Out yonder”, he says, “was this huge world, which exists independently of us human beings, and which stands before us like a great, eternal riddle. The contemplation of this world beckoned like a liberation. in which one might find “inner freedom and security”, indeed, a “road to paradise”. One has, perhaps, some misgivings about the “security” of this paradise, when he goes on to observe that “conceptual systems are logically entirely arbitrary”. “The concepts and propositions get ‘meaning’, viz. ‘content’ he says, “only through their connection with sense-experience. The connection of the latter with the former is purely intuitive, not itself of a logical nature. The degree of certainty with which this connection, viz., intuitive combination, can be undertaken, and nothing else, differentiates empty phantasy from scientific ‘truth.’ ”

Well, there is the paradise of scientific knowledge—at least one version of it. But is it really whole and complete and free and secure? Is it really, after all, a paradise? Most of our authors, it seems, would answer, “No”. Thus Albert Schweitzer, in his Strassburg Sermon, remarks: “Our knowledge represents an insight into insoluble contradictions. all of these originate in the one contradiction that the law according to which events take place contains nothing which we recognize as being moral and which we experience as such.” And Carl Jung, in his essay on “Spirit and Life”, speaks of “a kind of higher consciousness”, and says that “its inscrutable, superior nature can no longer be expressed in the concepts of human reason. Our powers of expression then have recourse to other means; they create a symbol.”

Here, then, is a conflict between the scientific and the humanistic spirit; and that conflict, in one form or another, seems to run like a thread through all the twentieth-century authors we have considered. Thus, when Alex Thio, the sociologist, writes about “Deviant Behaviour”, he speaks of a conflict between a scientific perspective which would see actions as environmentally caused, and a humanistic perspective, which would see the same actions in terms of “subjective experience, voluntary and self-willed”.

When Donald Grout writes about the revolution in twentieth-century music, he represents it as a conflict between the determinate logical forms of music, and a new aesthetic, whose principle is indeterminacy and whose method is randomness. It seems to end in “Feelings”. And when Solzhenitsyn writes on Soviet politics, there is the opposition between the confining, destructive ideology on the one hand, and essential human freedom and creativity on the other. In yet another form, Martin Heidegger represents the conflict, in his essay on “Building Dwelling Thinking”, when he argues that although technology may build a house, man can truly “dwell” only in terms of a deeper spiritual integrity in the felt presence or absence of the gods.

I suppose all this is what C.P. Snow sums up in his book about the “Two Cultures”; but the opposition is more dramatically represented by the artists. Wilhelm Bölsche, in “The Scientific Foundations of Poetry”, writing in 1887, remarks that “The natural sciences constitute the basis of all our modern thinking. This knowledge is increasing every hour, already now representing such a force of proof that the most decisive aspects of the older notions which man had formed about his own nature on the basis of less exact investigations must be discarded.” He looks forward to a fruitful partnership, with Science and Poetry “striding side by side”. Now, nearly a century later, surely that forecast seems incredibly naive. Less complacent about the prospects of any such reconciliation, Emil Nolde protests: “within a human being the intellectual always wants to be more clever than the artist. Intellect is for the creative man anti-artistic, intelligence can be a false friend.” And so, what Albert Einstein called the “merely personal” returns, with all the “wishes, hopes and primitive feelings” he sought to exorcize on his “road to paradise”.

Thus, Dostoevsky in his Letters from the Underground, remarks: “That two and two are four, I consider to be an excellent thing; but that two and two are five can sometimes be quite charming too.” And Unamuno, the great Spanish existentialist, in his Tragic Sense of Life, has this to say:

Man has been defined as a rational animal. I do not know why he has not been defined as an affective or feeling animal. I have never seen a cat laugh or weep. Perhaps it laughs and weeps secretly. But then, perhaps, also secretly, a crab resolves equations in the fourth degree.

This, then, is the theme I’d like to take up, and ask you to consider in historical perspective. In some ways, it’s a very elusive theme, with many forms and facets: it is the quarrel between the scientist and artist; between the claims of universal understanding and particular individuality; between objective forms of all kinds, and subjective freedom—there are many ways of describing it. Perhaps best to say that it is the conflict between the rational and affective elements in man’s very soul.

And though certain forms of it are new, and certain circumstances are new, the basic issue is by no means so. Surely the quarrel is already there in the early nineteenth century, in the Romantic Movement’s battle against the “rationalism” of the Enlightenment, and the Romantic’s claim for the primacy of “feeling”. But even then, it was not new: one could offer instances and illustrations from every time and place. Here are just one or two you might consider, chosen somewhat at random from texts which you have studied.

What, for instance, was the meaning of the thirteenth century argument between Thomas Aquinas and Bonaventure? You remember, perhaps, that the quarrel was about the fundamental nature of the science of theology. Was it to be thought of as primarily speculative or primarily practical—by which they meant, was it primarily intellectual or primarily affective? Is man’s destiny to be fulfilled primarily in knowing or in loving? Thomas answers that it is both; but because one can love only the good he knows, knowing has a certain priority of order. And I hope you remember how that position is worked out in the great drama of Dante’s Divine Comedy, where one comes at last to the vision of the Trinity, and sees that knowing and loving, logos and spirit, are equal and co-eternal moments of one divine principle. From that vision, looking back to the image of Satan in the frozen lake, one sees how for Dante the bottom of Hell is precisely the separation, the dissociation, of those moments. It is a problem about the nature of theology, certainly; but it is therefore also a problem about the nature and destiny of human personality.

But go a little further back—to St. Augustine in the early fifth century, and consider his complaints against the ideology of the declining Roman Empire. What is his complaint, really, but to say that the universal, impersonal logos of Rome has no place for the vitality of spirit. Against that logos, he asserts that the will is all-important. What matters fundamentally is the direction of one’s will, the direction of one’s love: “My love is my weight”, he says, “whithersoever I am drawn, I am carried there by love.” And in his great treatise On the Trinity, one sees how he understands those principles of logos and spirit reconciled; and in his City of God, one sees how that reconciliation becomes the foundation of a new era in the history of civilization.

But our problem does not begin with the ideology of Rome and the protest of St. Augustine; its locus classicus is the history of the literature of Ancient Greece. With certain of the nineteenth century Romantics looking at the history of Greek poetry, it became virtually a dogma that true literature had been destroyed by intellect, by critical reason, by philosophy. That dogma was repeated, and revised, by Nietzsche, and then by Heidegger. According to that view, Socrates is the villain. He is the prophet of critical, scientific reason, and the executioner of poetry: he is the prophet of technology, against humanity. One would not wish, I think, to subscribe in toto to that Romantic dogma. But it does at least contain this element of essential truth—the conflict of intellect and spirit is somehow there.

Book X of the Republic, you will recall, presents an argument in which Socrates proposes the expulsion of the poets from the commonwealth, except for those who “sing the praises of the gods and of good men”. I’d like to say many things about that proposal in the context of the whole argument of the Republic, but there isn’t time for that. Suffice it to say that it is not a proposal for totalitarian censorship in the state; it is a proposal for the subordination of spirit to intellect.

With this Platonic argument, we stand at a turning point in the history of thought and literature, and of that fact Plato himself was well aware: the Republic has a prologue in which that turning point is well described. The scene, you will recall, is Athens’ seaport, the Piraeus, and the occasion is the celebration of the Thracian moon goddess, Bendis, a new divinity from foreign parts. Socrates enters into conversation with three characters: Cephalus, his son Polemarchus, and Thrasymachus, on the subject of justice. Cephalus, an old man, preparing for his death, stands for the old piety. He has little taste for argument, and he soon goes off to offer his accustomed sacrifice, and bequeaths the argument to his son. Polemarchus is indeed prepared to argue, but unfortunately, he is confused. He takes his stand on a definition from the poet, Simonides, but when he is questioned, he is forced to confess that he has forgotten the meaning. Socrates suggests that the position has a certain basis in Homer, and also, in the end, betrays the character of despotism. Thus, the argument descends to the new man, Thrasymachus, the sophist, for whom argument can settle nothing, and is really just a form of entertainment.

What one sees here is the passage from belief, through confusion, to subjective scepticism; it is a history of enlightenment. What the old poets meant is now forgotten, and it is from just that point that the argument of Socrates must begin. The older world of belief, and the poetry belonging to that world are dead. As Plato remarks, in the Gorgias, tragedy now means only hedone—it is only entertainment, and has nothing to do with virtue. As Hölderlin, Heidegger’s inspiring poet, would put it, “my friend, we have come too late. Indeed, the gods live, but above our heads, up there in a different world.”

Only in the older world of belief—not dogmatic, certainly, but nonetheless consistent and secure—could the old poetry have its home. That was the matrix of its inspiration, and only there could its symbols—its imitations—immediately make sense. Criticism and self-conscious speculation, and in general the disruption of the community of belief, break that immediacy, and then poetic imitation is only images of images, capable no doubt of giving pain or pleasure, capable of entertaining, but embodying no sure truth. That is what Plato means, I think, in the Phaedrus, when, after discussing the divine inspiration of poetry, he remarks that among all the forms of divine possession, “philosophy alone has wings”. That is to say, only philosophy can transcend the images and recall the truth which lies behind them. The poet is ecstatic, possessed by the spirit, drunk with vision, and therefore he speaks with tongues, “in odes and other kinds of poetry”. But, says Plato, the poet does not remember the forms, and therefore speaks without the understanding. Such speech, as St. Paul would say, is “not good for the use of edifying”. Only philosophy recalls the forms, “only philosophy has wings”. Thus, even in the Phaedrus’ praise of poetry as divine possession, the quarrel with philosophy appears.

Once belief is gone, the poetry of belief lives only by philosophy. What is lost for belief is recovered only by theology. That is the meaning of the allegorical interpretation of Homer in Plato, and in all later Greek tradition: one can make sense of the poetry only through philosophy. And that is what Plato has in mind when he remarks, in the Republic, that Homer’s stories of warring gods will not be useful for the education of the young, because “a child cannot distinguish the allegorical from the literal sense”.

In the history of Greek literature, poetry precedes philosophy. With Plato, there is a turning point, and now philosophy must lead the way to poetry, and the philosopher must become a poet; not just by the allegorical interpretation of ancient authors, but also by a new poiesis of his own. Indeed, that is essential in the whole Platonic doctrine of the soul’s ascent. Once the philosopher has seen the good beyond the images, once he has been possessed by the divine, he is constrained to return again, right to the bottom of the cave, where are only appearances, only images of images, “third in succession from the throne of truth”; for it is there that the reform of souls begins, there is the starting point of all ascent.

According to the doctrine of the Cave and Line analogies, one moves from impressions of appearances to convictions about the images which appear, thence to discrimination of the formal structures of those images, thence to the forms themselves, and finally to the good. It is the ascent through belief to understanding; but it begins, and must begin, with the appearances. The philosopher, as poet, is therefore image-maker, concerned with the reform of the appearances, so as to move the prisoner of the cave to look beyond. Remember, he must be forced to turn around. He cannot simply be told the good—it would then be only an empty abstraction; rather, he must be moved through visible to invisible, through belief to understanding.

Thus it is that Plato, possessed by the vision of the Good, becomes image-maker and mythographer. That poetry which shows nothing beyond its images must be excluded as soul-destroying. But that poetry which reforms the images and moves the soul to seek the good, that poetry which recalls the forms, and therefore “sings the praises of the gods and of good men”, will remain essential to the soul’s true commonwealth. The poem inspires right belief, and with that belief begins philosophy’s ascent. Therefore, Plato concludes the Republic with the philosopher’s poetic fable, the “Myth of Er”.

Socrates is not the executioner of poetry: he is its would-be saviour. He seeks the reconciliation of intellect and spirit—the wholeness and justice of the soul. That is what the Republic is all about. But the only solution he can see involves the radical subordination of spirit to reason, and reason’s radical subordination to an absolute good which it can never understand.

That is really the beginning of a problem, and everything that follows serves towards fuller explication and deeper understanding of that problem. The problem is there in the beginning: all the essential problems are there. The history of thought and institutions is the story of their working out in various forms and circumstances.

I’m sure that many of you felt at various times, especially in the early sections of the Programme, that the relevance of what you were doing was pretty obscure. Perhaps it is true, as T.S. Eliot says, that in the end we come again to the beginning, and know the place for the first time. Perhaps it is only when we see these problems in the present that the relevance of the past comes home to us. The past is like the shades in Homer’s Hades: it speaks only when we give it our own blood to drink.

Well, we began with a twentieth-century problem—and what is the point of this long excursion into history? We cannot, after all, pick out ready-made solutions from other times and circumstances. In certain ways, our problems are our own. And yet, we do not start at the beginning. Because of Homer, we do not start where Homer started; because of Plato, we do not start where Plato started; because of Dante, we do not start where he did.

A great twelfth-century poet, Bernard Silvestris, says very well what I want to say: “We moderns are like dwarfs”, he says, “standing on the shoulders of giants; if we see more things than the ancients did, and things that are further off, it is not because we are taller than they were, or because our sight is better than theirs, but because they raise us up by their great height.”

Our problems are our own, and we must come to an understanding for ourselves; but I hope that we have found some giants to lift us up. Not those gross irrational giants, the Titans, who can only lift us down to the frozen lake of Cocytus, but giants of understanding, who can lift us up to see the far-off things. If we have met a few such giants, then this has really been a “Foundation Year.”

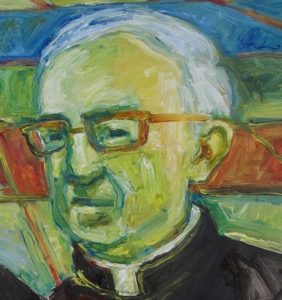

Dr. Robert D. Crouse was a Professor of Classics at the University of King’s College, Halifax. He was Director of the Foundation Year Programme in 1980-81. The image is a detail from a “Triple Portrait of Angus Johnston” by Jane Reagh. In that portrait (commissioned by Neil Robertson) Angus is figured with Robert Crouse on his left and James Doull on this right. This is a detail of Robert Crouse. The King’s archives have a full and vibrant portrait by Jane Reagh of the Rev’d Dr Crouse that has been deemed to be too startling for public display, or something like that. Thank you to Fr Ingalls for suggesting this lecture as a FYP Letter, and to Janet Hathaway for finding it for me in the King’s archives.

Dr. Robert D. Crouse was a Professor of Classics at the University of King’s College, Halifax. He was Director of the Foundation Year Programme in 1980-81. The image is a detail from a “Triple Portrait of Angus Johnston” by Jane Reagh. In that portrait (commissioned by Neil Robertson) Angus is figured with Robert Crouse on his left and James Doull on this right. This is a detail of Robert Crouse. The King’s archives have a full and vibrant portrait by Jane Reagh of the Rev’d Dr Crouse that has been deemed to be too startling for public display, or something like that. Thank you to Fr Ingalls for suggesting this lecture as a FYP Letter, and to Janet Hathaway for finding it for me in the King’s archives.