“In a sense, then, every escaping freedom-seeker was engaged in a right of exorcism to rid themselves of the monsters who violated their integrity, and the ghouls who ate up their substance and surplus.”

– Dr. George Elliott Clarke

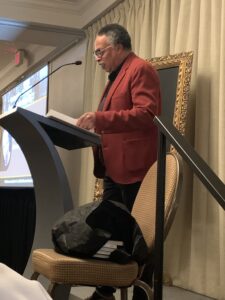

The Universities Studying Slavery Conference hosted by Dalhousie and the University of King’s College in partnership with the Black Cultural Centre for Nova Scotia marks a momentous step in unearthing the history of slavery across Canada, which was wrongly buried over centuries in efforts of active erasure and ignorance. On Friday, October 20, a vivacious and keen audience gathered to attend the evening’s keynote speech, delivered by the incomparable Dr. George Elliott Clarke.

Introduced by Reverend Dr. Rhonda Britton, Dr. Clarke is the 2016/2017 Canadian Parliamentary Poet Laureate, recipient of the Governor General’s Literary Award and the Portia White Award alongside many others, as well as the holder of eight honorary doctorate degrees (yes, you read that right). His many accomplishments recognize his powerful work, which radiates a passion for justice and storytelling.

Dr. Clarke received an informal introduction from Dr. Isaac Saney, who spoke to Dr. Clarke’s persona: down to earth, kind, with a wit like no other. I had the pleasure of meeting Dr. Clarke during the event, and from one conversation alone can corroborate these characteristics. He is, as Dr. Saney referred, a “tour de force” in the most holistic sense of the phrase.

Dr. Clarke received an informal introduction from Dr. Isaac Saney, who spoke to Dr. Clarke’s persona: down to earth, kind, with a wit like no other. I had the pleasure of meeting Dr. Clarke during the event, and from one conversation alone can corroborate these characteristics. He is, as Dr. Saney referred, a “tour de force” in the most holistic sense of the phrase.

Dr. Clarke opened his keynote speech with a compelling call to constitute a Nova Scotia slavery museum in Halifax, and framed his speech as a guide to the artifacts that would be housed within the museum. He presented these artifacts, which is a total composition that spans from 1713 –1840, and a product of his tireless research. From the description of ads for slave sales in Halifax, records of Black people being named as chattel and household goods, excerpts from The Book of Negroes, and proof of oppressive bylaws that aimed to dismantle Black community and culture, Dr. Clarke’s speech breathed life into a history that has been robbed of a voice.

With powerful cadence, he wove a tapestry of the resistance and survival stories of Black African Nova Scotians. The fibres of this tapestry included the names of these individuals, such as Mary Postill and Charles Benoit, and an honouring of their stories in detail. He emphasized that while the colonial government only provided rotten and non-arable lots of land to impoverished Black communities in Nova Scotia, these communities took those lots and built upon them lives rooted in resilience and faith. Claiming their agency in the face of racism, they even constructed what Dr. Clarke called “their own lingo of African Nova Scotian English.”

With powerful cadence, he wove a tapestry of the resistance and survival stories of Black African Nova Scotians. The fibres of this tapestry included the names of these individuals, such as Mary Postill and Charles Benoit, and an honouring of their stories in detail. He emphasized that while the colonial government only provided rotten and non-arable lots of land to impoverished Black communities in Nova Scotia, these communities took those lots and built upon them lives rooted in resilience and faith. Claiming their agency in the face of racism, they even constructed what Dr. Clarke called “their own lingo of African Nova Scotian English.”

Upon the conclusion of his speech, Dr. Clarke opened up the floor to the audience for questions. This was met with telling pause from the audience, as he had truly provided an in-depth, striking and meticulous account of Nova Scotia’s history systemic enslavement. A question did arise from a University of Ottawa student, who inquired into the relationship between the African and Indigenous communities in Nova Scotia. Having touched on this during his address including his own personal connection to Indigeneity, Dr. Clarke was grateful for the question and explained that the two groups have a long and intertwined lineage. He further explained that Black land allotments were often placed near Indigenous reserves, resulting in interaction and overlap between the two groups. There is much more to be unpacked in this area of intersection.

The historical tapestry created by Dr. Clarke’s keynote, coloured by names, dates, archival records and more, impactfully subverted the all-too common assertion that claims Canada never had slavery. Condemning the “Machiavellian malfeasance” of Nova Scotia’s roots as a slave state, Dr. Clarke shone light on pieces of history long buried in the shadows. A means to further shine this light is Dr. Clarke’s proposed Nova Scotia Slavery Museum. He gave the audience a potent framework to imagine it, and I have a deep hope that one day we will see it tangibly brought into being.