Each month, we ask a member of faculty to tell us about one book that played an outsized role in making them who they are today. For this month’s Words to Live By, assistant professor of journalism, Tim Currie reflects on a book he read many years ago and whose lessons bridge great research and great storytelling.

What book have you chosen?

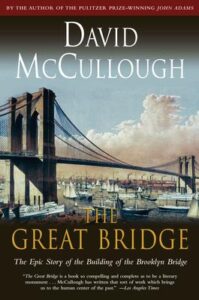

I’ve chosen David McCullough’s The Great Bridge, a nonfiction book about the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge in the 1870s. McCullough was a Pulitzer Prize-winning author of popular American history who passed away about 18 months ago. He was acknowledged at his death as both a master storyteller, but also a historian who offered a somewhat blinkered view of American history.

I’ve chosen David McCullough’s The Great Bridge, a nonfiction book about the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge in the 1870s. McCullough was a Pulitzer Prize-winning author of popular American history who passed away about 18 months ago. He was acknowledged at his death as both a master storyteller, but also a historian who offered a somewhat blinkered view of American history.

When did you first read this book?

The book was first published in 1972. I read it more than 20 years ago, not long after my now-wife and I walked across the bridge. We had marvelled at its beauty on a brilliant afternoon mere weeks before 9/11.

Was it a book that you read quickly or did you take your time reading it?

I’m not a particularly quick reader. So, at 562 pages, the book probably took me a month to get through. It is a story of grand human endeavour and also intricate engineering challenges. I found it deeply engrossing, but best enjoyed in short bursts.

What was it about the book that first stood out to you?

The research. Documentary filmmaker Ken Burns is quoted as saying McCullough “taught me how to tell a story.” McCullough uses meticulous detail from board meetings, newspapers, personal diaries and hundreds of other sources to build a riveting narrative. The chapter “Wire Fraud”—about the numbingly boring topic of steel cable procurement—begins with workers risking their lives to secure broken strands whipping a half-completed tower during an icy storm in January 1878. What follows is a fascinating story of tragedy, corruption and scandal.

Have you reread this book? If so, did you get something different from it on rereading?

I haven’t reread it. But I recently flipped through McCullough’s chapter on Emily Warren Roebling, the wife of bridge engineer Washington Roebling, after watching a December 2023 episode of HBO’s The Gilded Age. A character in season two refuses to publicly “reveal” that management of the bridge’s construction was “largely the work of a woman” (Emily) after Washington was critically injured on site in 1872. McCullough calls Emily a “remarkable person” deeply involved in the project, but one who “did not, however, secretly take over as engineer of the bridge, as some accounts suggest.” Really? I gather the HBO producers took their cue from Pace University history professor Marilyn Weigold, who called Emily a ”surrogate chief engineer” of the project in her biography of Emily, published a decade after McCullough.

How did this book shape you?

I loved this book at the time. I think about it often as one of the most satisfying books I’ve read. It gave me a deep appreciation for how research can make a good story a great one, by bringing scenes and characters to life. The book also prompted me to read more by David McCullough — 1776 on the lead-up to the American Revolution and The Path Between the Seas on the construction of the Panama Canal. The Great Bridge ultimately gave me a more critical perspective on popular history and who writes it. McCullough’s books offer a rather antiquated view of history focusing on the resilience and grit of influential American men. In the Washington Post, University of Kansas history professor Andrew C. Isenberg cast a disapproving view, calling a later book by McCullough “a grand civics lesson, in which the accomplishments of our principled forebears serve as inspirations.” Harvard professor Joyce E. Chaplin, in the New York Times, termed it dryly as “American history as a vision of our better selves.”

What do you think it is about this book that made such an impact?

I find American history fascinating. This book touches on the nonfiction themes I love: politics—the coercive force of Tammany Hall in 19th-century New York. Social justice—the bitter fight for labour rights of immigrant workers. And science—the complex engineering challenges of building caissons in the frigid East River.

Who do you think should read this book?

Anyone with a love of history would enjoy the book, if only for the grand story it relates. Just know the book—and McCullough himself—were firmly the product of their time.