Director of Writing & Publishing Gillian Turnbull shares the backstory of a new book about writing—or, more accurately, about not writing—that she co-edited with three fellow King’s alumni.

Anyone who’s arrived on the King’s campus for the first day of class knows the feeling of trepidation, of anticipation. Lingering summer heat on the “mini quad” in Willwerth Garden, long fingers of grass swaying in the wind, quiet murmurs among clusters of chatting students. The air electric with potential. That was certainly how I felt when I made my way outside to the gathering mass of Master of Fine Arts students in August of 2015. As we edged into conversations—“What is your book about?” “Where are you from?”—I knew I’d found my people.

There’s a photo circulating in our files of the first group I approached. Sandy MacDonald, MFA’17, MJ Grant, MFA’17, and Pamela Oakley, MFA’17, among others, listening intently to each other, sticky nametags splayed across their chests. I had no idea then that these three writers, along with Nellwyn Lampert, MFA’17, and Christian Smith, MFA’17, would be my closest confidants nine years later.

After the intensity of the residency, we returned home, which for MJ, Nellwyn, Christian, Pamela and me was Toronto. Somewhat rudderless without the structure of weekly classes, we decided to meet regularly and share fragments of our manuscripts as they inched toward completion. We rotated hosting duties. There was cheese. Wine. MJ’s husband’s famous gin and tonics. Once, Christian brought a microscope and display screen to show us the HeLa cancer research cells discussed in The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, a book we’d all read for the program. We met Pamela’s dog, also named Nellwyn, along with all the other pets: Puffin, Madeline, Kay, Afra, Pumpkin, Martie, Emily and Geddy.

As the pandemic set in, we moved from in-person to online, from a monthly schedule to weekly. We clung to these Friday morning Zooms, all fighting the panic of writing blocks and expectations to produce. Passing productivity guides to each other—Cal Newport’s Deep Work, James Clear’s Atomic Habits, Oliver Burkeman’s Four Thousand Weeks—we spent more time on writing strategies and to-do lists than writing itself. Christian posted a memento mori on his wall, marking off the weeks that ticked by without additions to his manuscript.

Fed up with the dread, I proposed we put together a different kind of book. This one would be about not writing—contradictory, I know. We needed the balm of conversation with other writers who were also not producing. Unlike the Newports of the world, most of us didn’t have structural supports to facilitate a consistent, methodical writing practice. Chronic illness, a negative balance in the chequing account, disability, the demands of parenting, all disrupting a continuous flow of inspired words. Surely, there were others out there like us?

We put out a call. Tell us about your relationship to creativity, we said. Is it being destroyed by the command of capitalistic productivity? Where has your free play gone, what dissatisfying results appear on the page after you force out your pre-planned word count for the day? Where are your artistic inputs? What other pastimes might feed your writing instead of the blinking cursor on a word document?

Well. Essays flooded in, with references to quitting writing for good. Exhorting us to embrace the fallow periods, much like a gardener does to replenish soil’s nutrients. Asking, what if children led us back to the wonder of observing and creating? Wondering, how about we just slow down?

By this point, our group had dwindled to four. Several of our friends had responded to the call of other obligations and filtered away, but Nellwyn, Pamela, Christian and I continued to meet. Our idea turned into a plan, and a plan turned into a book. We are bad artists, I said, if our worth is measured by our output. But what if, like so many “bad” writers before us, we wore that label with pride?

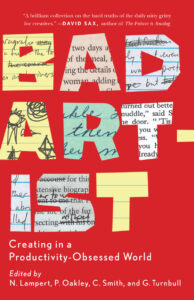

Bad Artist: Creating in a Productivity-Obsessed World is our tiny form of resistance, not only to the demands the modern economy makes on artists, but also to the idea that creativity happens in a vacuum. The best art, we argue, is collaborative, social, supportive, compassionate—just like our MFA experience was. The magic of the program wasn’t simply that we left with a manuscript, it also gave us the artistic family we’d all been searching for.

Perhaps it should have been obvious to us that such an environment would naturally lead to collaboration in the form of a book. We’d never seen a book with four editors before, nor had any of the publishers we pitched. But TouchWood editions trusted that we knew each other and our contributors—all 17 of them, many also King’s alumni and faculty—and took a chance. The result is our book, a work of art, that captures that trepidation, excitement, potential of our first day along with nearly a decade of artistic friendship. Perhaps we aren’t bad artists after all.

Inset photo: Gillian Turnbull, Director of Writing & Publishing

Bad Artist: Creating in a Productivity-Obsessed World

Bad Artist: Creating in a Productivity-Obsessed World

Edited by N. Lampert, P. Oakley, C. Smith and G. Turnbull

The perfect antidote to the toxicity of the current productivity narrative, this collection of essays on creativity features 21 Canadian and international writers, providing warmth, support, camaraderie and empathy.

Toronto Book Launch:

September 25, 7 p.m.

Danu Social House

Halifax Book Launch:

October 17, 7 p.m.

The Bus Stop Theatre