FYP Letters is a series of non-curricular notes to keep us in touch over the next days and weeks. They are a combination of original writings and archival ones, including some re-printed FYP News items. — Dr. Susan Dodd, Interim FYP Director.

Why Gawain?

The curriculum in FYP is constantly morphing and changing, usually not radically, but by adding this new text, or taking that one out. All coordinators are working within a very limited set of parameters—as coordinator of the Middle Ages section, I decided to keep Dante, one of the most stable elements in the FYP reading list since its inception; and to make Saint Augustine’s Confessions the centre of the account of how the west became Christian—another pillar of the course. Presto: eight of the section’s fourteen lectures decided at the outset. Then it is a matter of choosing between many worthy and extraordinary texts for the remaining six. This year, as a parting gift to the program, I decided to add the anonymous Middle English poem Sir Gawain and the Green Knight for the final day of the section.

At first I thought this choice might be a bit self-indulgent. SGGK is a canonical text in my field of scholarly training and research, very well known to English students, but little known, as it turned out, to people outside the discipline. As out-going coordinator and now semi-retired professor, I indulged myself.

Sir Gawain is a strange mixture of archaisms and traditional medieval story forms with a new, decidedly late medieval, view of the human individual as marred, isolated and internalized, as an ethically responsible subject. The poem falls in the very broad category of Arthurian literature, as do some of the much earlier lais by Marie de France that we also read this year. It is composed in alliterative verse, an archaic poetic form that ties the rhythm together with stress patterns on the same sound. In its original English, it is a mighty sonic accomplishment, highly beautiful, and, in the hands of this poet, capable of striking onomatopoeic effects. However, modern English followed the London high street of this poet’s exact contemporary, Geoffrey Chaucer, so we read the poem in translation. Even so, the beauty of the effects, not to mention the extremely clever plot (which I will not spoil here), came across very well.

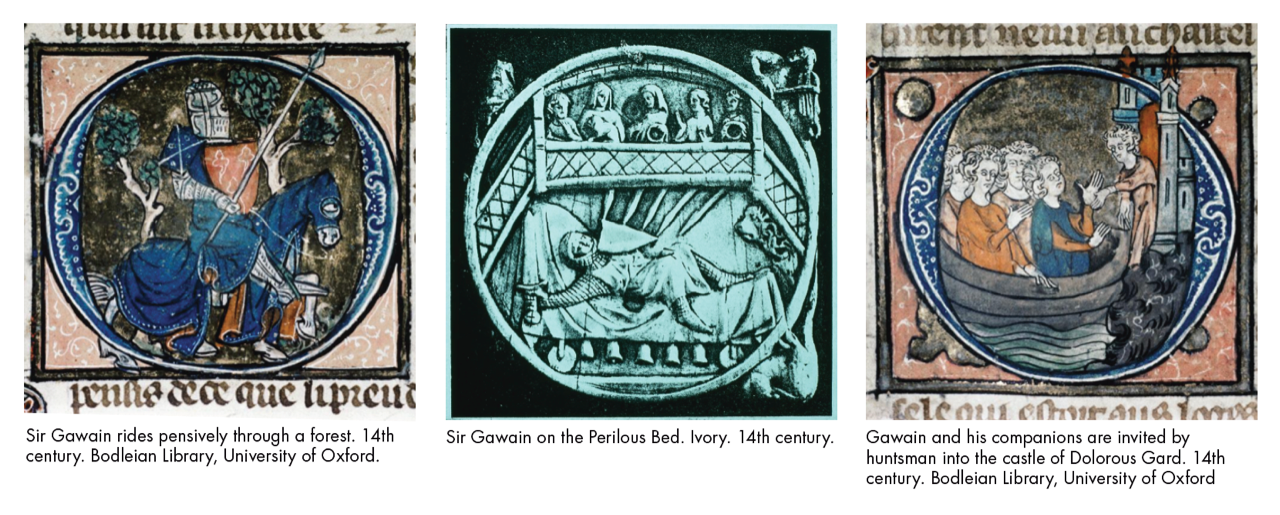

The poem begins with a beheading game. A supernatural green visitor interrupts the New Year’s games at Arthur’s court, with an offer to exchange a blow to the neck with any knight hardy enough, the strike to be exchanged a year later. Gawain accepts the challenge, only to find that the green knight can pick up his head and ride off after being beheaded; the playing field, then, does not appear to be level. The great thematic structures of the poem concern games and their strategies, courtly behaviour and the perfection of chivalrous manners, contracts and bargains of a surprisingly commercial nature, and a quest for knightly perfection in the intertwined virtues of Gawain, “the pentangle knight.” While the marvels and magic, no less than the traditional material and Arthurian setting, tend to situate this drama in never-land, the consideration of “troth” (truth), the quest for ethical perfection, and the individualism of that quest, as well as the fourteenth-century commercial, context instead make this text a transition to the next section, to a new conception of the human.

To put it very colloquially, when introducing new texts into Foundation Year, the question is always ‘is this book great enough for a great books program?’ I believe that this work has spoken for itself.